“But a thighbone or so,” was how poet Robinson Jeffers put it. That’s what he expected to be left of our great civilization a few thousand years from now. Ed Abbey pictures us surviving, but differently—he sees a day when blue-eyed Bedouins will herd their sheep past the great and mysterious ruins of concrete dams.

Carl Sagan, on the other hand, tried to look into our future by looking out, at the stars.

We all know and love—and make fun of—Carl Sagan as the popularizer of science, but he was actually a very interesting man. He was an advisor to NASA from the nineteen fifties onward, and we all remember him as the face of space exploration on our TV sets. Every comic in the world has had some amount of fun with his phrase, “billions and billions,” and he always took it with great humor (though he never said exactly that—the closest he came in his TV series “Cosmos” was “billions upon billions”). What people tend to forget, though, was that he was also a brilliant scientist and social thinker, and with an impressive conscience on board.

He would tell you that two opposing forces guided his life: a sense of wonder about the universe, and a skeptical thought process when investigating it. One of them, he felt, was no good to you without the other, and that is the paradox that made the man: The scientist willing to go out on a limb and turn the search for extraterrestrial creatures into a mainstream science, also held skepticism to be a personal ethic. It used to be thought, for instance, that the planet Venus had a balmy, paradise-like climate until Carl Sagan ran the numbers. He came up with a surface temperature of 900 degrees Fahrenheit, and was later proven right by the Mariner spacecraft. It was Venus that got him interested in global warming—he realized that that planet is one giant case of runaway greenhouse warming.

But his epiphany regarding the future of the human race came via a mathematical equation called the Drake Equation. The Drake Equation looks like this:

N = R* ∙ fp ∙ ne ∙ fl ∙ fi ∙ fc ∙ L

where:

N = the number of civilizations in our galaxy with which communication might be possible;

and

R* = the average rate of star formation per year in our galaxy

fp = the fraction of those stars that have planets

ne = the average number of planets that can potentially support life per star that has planets

fℓ = the fraction of the above that actually go on to develop life at some point

fi = the fraction of the above that actually go on to develop intelligent life

fc = the fraction of civilizations that develop a technology that releases detectable signs of their existence into space

L = the length of time for which such civilizations release detectable signals into space

It is an interesting equation with an interesting mission: It attempts to calculate the number of detectable technological civilizations that should exist in our Milky Way galaxy. And when Carl Sagan ran those numbers he was astonished. No matter what reasonable numbers he plugged into that equation, the conclusion was the same: We should be awash in intelligent radio signals. And we’re not. We’re all alone. His conclusion?

Civilizations don’t last long.

He spent the last half of his career working to prevent the same fate from befalling this civilization. He was the one who realized that a nuclear exchange would be even more hideous than we were already assuming. It would put enough fine particulate matter into the upper atmosphere to create what he called a nuclear winter, lasting years, or decades. It was such a winter that killed the dinosaurs in the Cretaceous-Tertiary Extinction, caused not by nuclear explosions but by an asteroid impact where the Yucatan Peninsula is now. He also worked on that problem, advocating an organized search for near-earth objects that could impact our planet. When someone suggested creating nuclear devices capable of deflecting them away from the Earth, he pointed out that to be able to deflect it away from us was to be able to deflect it toward us, and then you have a doomsday weapon, which, in his opinion, we already had way too many of.

-

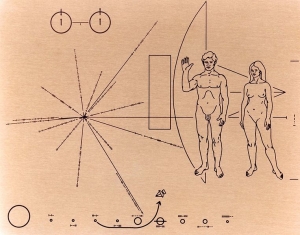

Carl Sagan was central to adding a plaque to the Pioneer spacecraft as a greeting to other civilizations

He tirelessly promoted an organized search for extraterrestrial intelligence, and finally got it some respect when he got seventy scientists, including seven Nobel laureates, to sign a petition published in the journal Science. That was the birth of his project SETI, which was among the first projects to develop “distributed computing”, using volunteer home computers across the world-wide web to do the prodigious number crunching necessary. It was one of the key projects that ushered in the era of “citizen science,” which can now be found everywhere. Now you can even enter your bird sightings into the website of the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, where they become part of an amazingly detailed database of bird distribution and movements.

He became an anti-nuclear activist. He considered Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative to be absolute madness, and was arrested twice climbing a cyclone fence with other demonstrators to attempt to occupy a nuclear test site in Nevada.

He considered the idea of a male, human-like god to be silliness, but did not distain the religiously minded, and hated to be called an atheist. Skeptical even about atheism, he pointed out that an atheist knows that there is no god. “An atheist,” he said, “has to know a lot more than I know.” He wrote the popular novel, “Contact,” where he works a lot with the interplay between science and religion. I will always remember the scene in that book, set after hours in a natural history museum, involving a physicist, a priest and a Foucault pendulum. The scientist volunteered to put her nose exactly where she knew the laws of physics would cause the great ball to stop, if the priest would put his a foot closer and pray for divine intervention. (The priest took her up on it, but then flinched, and was very disappointed in his own lack of faith.)

Carl Sagan died at only 62 years of age, after a long fight with myelodysplasia, and never saw that book become the Jodie Foster movie. The kid from Brooklyn who started going to the library because none of his friends could tell him what a star was, touched all our lives, even those of people who have not heard of him. He received many awards and accolades in his life, including the Public Welfare Medal from the National Academy of Sciences. (Mind you, that academy never awarded him a membership, considering his well-publicized media activities to be a bit unseemly.) Isaac Asimov said that he was one of only two people whose intellect surpassed his own, and to get a concession like that out of Isaac Asimov is indeed an accomplishment. My personal favorite, though, is that his fellow astrophysicists have named a unit of measurement after him. A Sagan of something is four billion or more of it—the word billions by definition being two billion or more, making billions and billions at least four.

So I am raising a glass to Carl Sagan tonight—a very interesting man who lived in very interesting times. To grow up in the space exploration age was to grow up with Carl Sagan. I will remember his goofy face imparting his sense of wonder to us all over the TV set as the data and footage started to stream in from each new space mission. And I will remember him for his conscience, his activism, and his work to make this civilization a success.

But to be perfectly honest, for myself I might prefer Robinson Jeffers’ vision of our future. A world without us might, I think, be a better place. So that’s the image I’ll leave you with: A thigh bone or so…here and there a rust stain on a mound of plaster.